Compton Cowboys: Book explores why they ride

Walter Thompson-Hernández was 6 when he 1st noticed the black cowboys of Compton, and he was fascinated. “They appeared ethereal — like superheroes on the again of mystic creatures,” he writes in his new book, “The Compton Cowboys.”

He grew up just a several miles away in Huntington Park, but his primarily Latino neighborhood was a world aside from Compton. When his mom drove to the Compton Swap Fulfill on weekends, she made confident that the motor vehicle home windows were being shut and the doors locked for anxiety of criminal offense. It was a baffling information for Thompson-Hernández, who says he was getting advised that Black persons were being risky, even even though he is of both equally Mexican and African American heritage.

Timothy Harris, a buddy of the Compton Cowboys, talks with Future Watson, seven, and Andrew Evans, eight, when collecting with other equestrian supporters from around Southern California just before a Peace Ride by way of Compton.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Moments)

Thompson-Hernández, who joins the Los Angeles Moments E book Club for a virtual meetup June 24, traveled the world as a reporter for the New York Moments, documenting very little-acknowledged subcultures such as the persecuted albino community of Ghana and woman rappers of Oaxaca, Mexico. But he was drawn again to his Southern California roots to immerse himself in the world of the new Compton Cowboys, a team of younger African Us citizens who locate healing and hope on the again of a horse. Their motto: “Streets lifted us. Horses saved us.”

In recent times, Thompson-Hernández, a multimedia journalist based in Los Angeles, has been out reporting on civil legal rights demonstrations in the region, and the cowboys have been using, urging their followers on Instagram to “be intelligent and harmless in accomplishing our goals.”

Keenan Abercrombia, a member of the Compton Cowboys, just before departing on a June seven Peace Ride by way of Compton.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Moments)

“I think what the past several months have genuinely underscored is that it’s even now in the end an amazingly risky and a violent location for Black Us citizens,” mentioned Thompson-Hernández. “It made me think about the destinations that Black Us citizens in the course of time — and primarily ideal now — have had to forge in the world or their communities to locate safety.”

For the Compton Cowboys, that location is Richland Farms, an oasis in the heart of urban Compton, exactly where African American cowboys have been welcomed due to the fact the 1950s.

Anthony Harris and Dakota on the Richland Farms ranch.

(Walter Thompson-Hernández)

The book tells the stories of 10 present-day Compton Cowboys — 9 men and just one female — who uncovered to trip as children in what was acknowledged as the Compton Jr. Posse. The using method was set up in the mid-eighties as an different for younger persons at possibility of gang violence and other perils of the streets.

As they grew older, some drifted away, pursuing competitive sports activities or setting up people of their own many others turned to gangs or medicine. But for each and every of them, “There was this minute in their lives when they missed that experience and that relationship to these animals — these genuinely compassionate, caring animals that in so lots of distinctive approaches provided a basis for healing,” Thompson-Hernández says.

Taylor Rahye Wade, 3, rides with her grandmother, Jennifer McClendon, in assistance of the Cowboys all through the Compton Peace Ride.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Moments)

Interacting with the horses, on their own generally victims of abuse, has served the cowboys recuperate from traumatic episodes in their lives.

Thompson-Hernández writes of cowboy Anthony Harris, who was jumped into a gang at age eight, fired a gun by 10 and was in jail at eighteen. Struggling by way of the isolation of a two-calendar year jail sentence on a drug conviction, Harris started to attract images of wild horses, coloring them with dye he made from Skittles candy. When he was launched, he found his way again to the ranch.

Audience also satisfy Keiara, the only woman member of the team. A competitive rider, she’s had to overcome not only an injuries experienced in a motor vehicle incident but also a heritage of trauma — a dysfunctional family members, sexual assault and the killing of her brother. She finds hope and indicating by way of her love of horses and rodeo competition.

The Compton Cowboys, with Randy Hook using lead, get ready to depart Gateway Towne Centre for a Peace Ride, culminating at Compton City Hall, on June seven, 2020.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Moments)

The tale results in being tense at situations as cowboy Randy Hook normally takes the reins of the corporation and tries to steer it in a new way. He has an bold eyesight of performing for social justice by connecting Black rider communities across the state. But Hook struggles to locate the resources needed to sustain the farm, and he clashes with his aunt Mayisha Akbar, founder of the Compton Jr. Posse, who looks unwilling to give up command.

Thompson-Hernández, who put in a calendar year and a fifty percent embedded with the team, says several of the cowboys advised him they generally experience safer using their horses on the fast paced streets of Compton than they do going for walks on the same streets.

As for the police, a scene close to the book’s conclusion is telling. An African American officer pulls up in a squad motor vehicle, dome lights flashing, tells the cowboys to “pull around,” and asks with a grin what they are doing on horses. “Nobody — together with myself — laughed at his joke,” Thompson-Hernández writes.

The Compton Cowboys trip down South Tamarind Avenue, along with protesters, all through the Compton Peace Ride.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Moments)

One particular of the cowboys’ missions is to reverse a Hollywood-engineered stereotype that makes bystanders glimpse twice when they see a Black guy or female on a horse. In truth, there were being hundreds of Black cowboys across the West in the several years immediately after the Civil War, and African Us citizens who migrated from the rural South immediately after Planet War II generally introduced their love of horses with them.

Now, the coronavirus pandemic has additional a different impediment to the cowboys’ work to preserve Richland Farms and bring in a new generation of younger persons by creating using interesting yet again. “This pandemic has genuinely impacted the ranch and their youth method,” Thompson-Hernández says. “Financially, they’ve taken a large hit. Persons have been furloughed, and they have had to offer a several horses.”

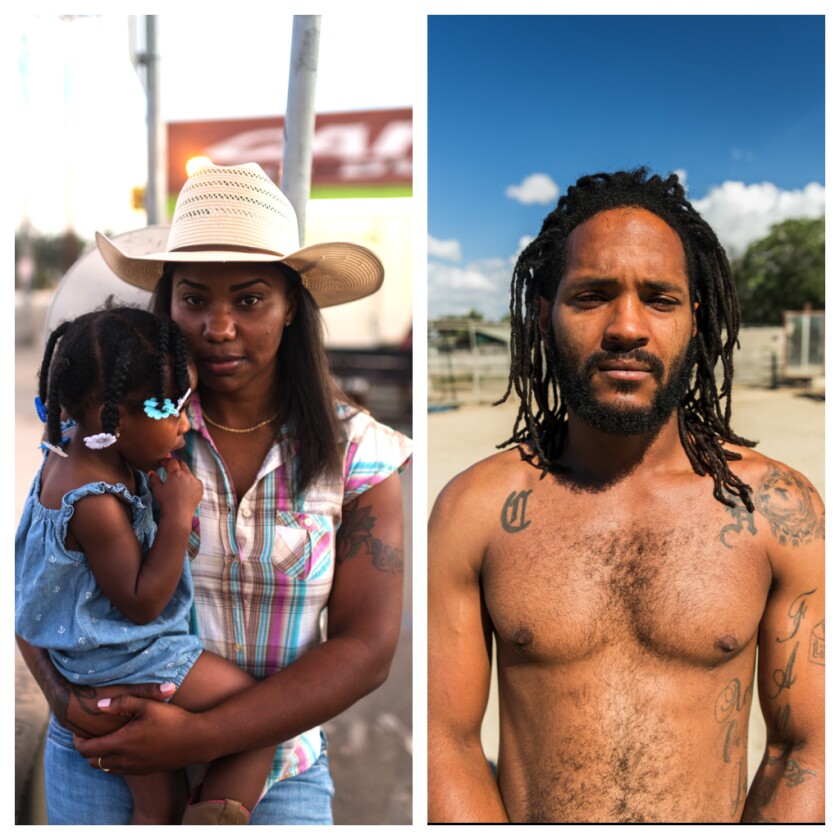

Compton Cowboys customers Keiara, remaining, with her daughter, Taylor, and Carlton Hook on the Richland Farms ranch, from the book “Compton Cowboys.”

(Walter Thompson-Hernández)

In his operate, Thompson-Hernández says he attracts on his background as an ethnographer, possessing acquired a master’s degree in Latin American reports from Stanford. When he feels privileged to have traveled the world as a journalist, the operate on the book was literally a homecoming, as he stayed in his childhood dwelling when doing analysis nearby.

“Being in Compton every single day to publish this book was a reminder of my childhood and of the pals who I the moment remaining,” he mentioned. “The cowboys introduced me again dwelling and reminded me of who I am and who I was.”

Fresh new off his 1st book, Thompson-Hernández has signed a contract to publish a memoir, tentatively titled “Belonging,” that will check out his upbringing by a solitary mom and his drive to check out cultures on the fringes of modern society. He is finishing operate on a 7-episode podcast for KPCC-FM (89.3), “California Love,” about Los Angeles and his experiences in the metropolis, established to debut in early July.

Associates of the Compton Cowboys wait outside a restaurant in Compton, from the book “The Compton Cowboys.”

(Walter Thompson-Hernández)

If You Go: E book Club

Walter Thompson-Hernández, creator of “The Compton Cowboys,” joins the L.A. Moments E book Club in conversation with reporter Angel Jennings.

When: seven p.m. June 24

Wherever: Totally free virtual celebration livestreaming on the Los Angeles Moments Facebook website page and YouTube.

Additional information: latimes.com/bookclub

Bio: Walter Thompson-Hernández

Journalist Walter Thompson-Hernández

(William Morrow)

Born: 1985 (age 35)

Lifted: In Huntington Park by a solitary mom who labored as a lodge parking attendant when finding out for her Ph.D. in literature. His father, a university professor, was absent from his early daily life.

Education: College of Portland master’s degree in Latin American reports from Stanford College. Further graduate operate at UCLA, in the Chicano reports Ph.D. method.

Background: Played specialist basketball for three several years in Latin The united states. Labored as a method counselor for two several years in a Los Angeles-place psychological health and fitness hospital. Labored for two several years at the New York Moments, composing and using photographs as section of the “Surfacing” staff, covering subcultures and marginalized communities around the world.

Present tasks: “California Love,” impending podcast series on KPCC-FM (89.3). Forthcoming memoir, tentatively titled “Belonging.”

Received: Whiting Imaginative Nonfiction Grant for his book “The Compton Cowboys.”

Twitter: @WTHDZ.

On the world-wide-web: wthdz.com/