Within weeks of Rochester musician Zahyia releasing the music video for her new single “Foul SoulChild” this spring, it had hit almost 50,000 views. The slow-burning, catchy R&B song features stripped-down production — a haunting keyboard riff, an addictive drum beat, and Zahyia’s voice echoing overtop, as if traveling from another world.

Wearing shimmering, bandage lace-up, knee-high boots and a matching corset, Zahyia moves alone in a stark room, dimly lit by dark blue and red light. Then, suddenly, she stands before a mirror, electric hair clippers in hand, and shaves her head in real time.

The singer, whose full name is Zahyia Rolle, says the act was one of the most significant parts of the video.

“I love my hair,” Rolle says. “But sometimes when I feel my body and my energy and my spirit going into a different place, and transitioning someplace new, I feel like I have to remove myself of the old energy.”

In the song Rolle sings honestly about her struggle with depression, while also addressing the struggle she witnessed other women in her community face in the past year. The battle includes dealing with burnout and mistreatment, and the desire to escape from a negative emotional space. It’s about overcoming what she refers to as a “toxic entity,” the “Foul SoulChild.”

“We don’t want that child to grow into an adult,” Rolle explains. “We need it to stay small, handle it, transform it into something positive.”

For Zahyia, the act of going bald symbolized moving into a period of health, hope, and wellness. For a growing number of Black women, it is a ritual deeply tied to reclaiming their cultural identity and rejecting white, Eurocentric standards of beauty.

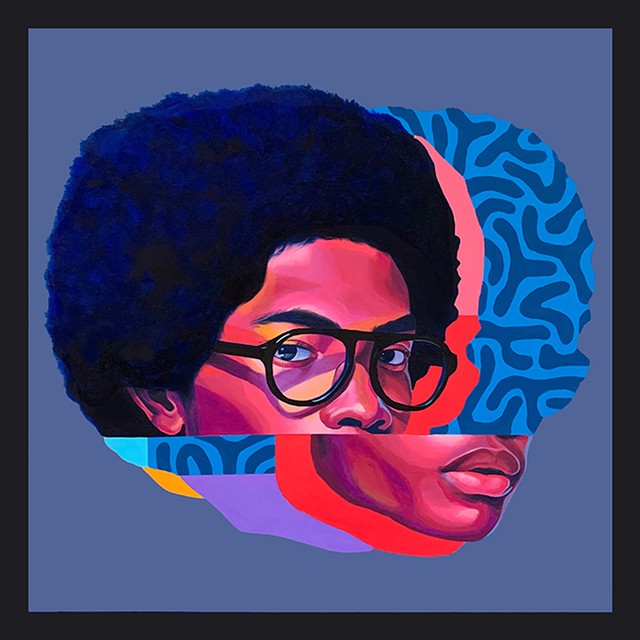

The work of several Rochester artists actively reflect this shift starting fresh and embracing natural Black hair.

The big chop

Over the last dozen years or so, a growing number of Black women have removed their chemically-treated hair and started their hair growth anew, affirming their identity in the process.

The “Good Hair” Study, a research project of the Perception Institute, which aims to reduce bias and discrimination, found the market value of hair relaxers declined 34 percent between 2009 and 2016. The trend is still going strong. Last year, Emmy and Grammy award-winning comedian Tiffany Haddish shaved her head on Instagram Live to the surprise and delight of fans and fellow celebrities.

For these women, “the big chop” is a rite of passage. It’s exactly what it sounds like; a big haircut. The bigness is both physical and metaphorical. How much hair goes depends on its length and how recently it had been permed or relaxed. But the decision is also big, and often rife with emotions.

“A lot of women have anxiety around the big chop,” says Rochester master loctician and natural hair stylist Niema Neteri, who, as the owner of Neteri Naturals, has helped guide many women through the process.

“A lot of our identity is tied to our crown, our confidence, and what we feel that we can do,” Neteri says. “A lot of women value length as being feminine.”

There’s a story behind every hair transition.

“I actually shaved my head every time I’ve had a child,” Neteri says. “When you’re growing a child, the hair is lush, it’s full — you’re taking your prenatal vitamins — and it’s thick, and it’s just shiny. And then once you give birth, and then I’m nursing too, so I’m depleting my body of all types of nutrients, right? and The hair tends to thin along the hairline. And I said, ‘Why try to save this? Let me just shave it off.’”

For Rolle, cutting off her hair has also been a recurring part of her journey.

“This is actually the third time that I’ve shaved my head in my life,” she says. “I love my hair, but I love my head — India Arie, like, we are not our hair, even though it’s such a huge part of our culture.”

Reclaiming Black beauty

The first wave of the natural hair movement emerged in the 1960s as a counter to standards of beauty that dominated Western culture — features that occur naturally in white people. Long, straight hair was rewarded, while Black natural hair was deemed undesirable.

As an outgrowth of the “Black Is Beautiful” movement, Black women and men styled their hair in Afros to signal their support of the civil rights movement, and affirm and celebrate their Black identity. It was a self-determination of beauty ideals.

“We were just embracing the African aesthetic, and wearing our hair because it defies gravity,” Neteri says.

Backlash soon followed, however. Police targeted and harassed Black people who wore Afros. Black political activists like Angela Davis were depicted on posters as enemies of the state. By the late ’70s and early ’80s, the style had become downright dangerous for Black people to wear, and its popularity dwindled. Later, the look was adopted by non-Black people, which led to further indifference.

Meanwhile, other Black natural hairstyles, like braids, were condemned as unprofessional in workplaces, and chemically-treated styles like the Jheri curl and Wave Nouveau began to replace them.

The new natural hair movement

In the late ’90s and throughout the aughts, a new wave of the natural hair movement emerged, this time inspired by a healthy and holistic approach to self-care rather than politics.

A whole genre of media — from forums and YouTube to blogs and books — sprang up to connect a new community of Black women learning how to style their natural hair. The affectionately dubbed “naturalista” community became a beacon of solidarity and sisterhood for many Black women.

“There’s these beautiful elements of our ability to bond with our sisters,” Rolle says. “Sometimes I feel like that’s the first thing I know I can connect with another woman who I don’t know. I’m like, ‘Hey girl! Ooh, your twist out is that—’ you know, like, ‘Oh, I know, that took a lot of time, you look amazing!’ It’s an instant connection with other Black women. It’s a bonding experience with mothers and sisters.”

Local athlete-turned-artist Brittany Williams celebrates natural hair in much of her work.

“Sometimes I use certain hairstyles as a push-back, because certain individuals expect something that’s more digestible when viewing art,” Williams says. “Eliminating the standard of being ‘presentable’ is always the goal.”

Williams’s work also brings Black men into the fold. She created the “Hair Don’t Lie” series in 2014 to champion Black athletes for their physical appearance and the personality conveyed by their unique hairstyles.

“I feel like Allen Iverson and Dennis Rodman paved the way for players to be themselves, regardless of what rules are put in place,” she says.

Despite the freedom of expression and bonding that have resulted from the newest iteration of the natural hair movement, old pressures still exist. They just appear in new forms.

Hair anxiety was a key concept of the “Good Hair” Study, which set out to determine whether and how bias affected perceptions of beauty and professionalism. The study found Black women experience more anxiety related to their hair, and greater social burdens of hair maintenance, than white women. For example, Black women were more likely to report spending more time and money on their hair, and one in five of them reported feeling social pressure to straighten their hair for work, twice as many as the white women in the study.

A criticism of the natural hair movement has been that light-skinned women tend to be the face of it. Another is the rise of what is known as “texturism,” in which looser curls and finer hair are favored over more tightly wound curls. Depending on the natural texture of one’s hair, which varies widely, some of these styles can be difficult and time-consuming to achieve.

“It’s almost sometimes like a double-edged sword,” Rolle says.

She says the number of hours she’s spent styling her daughters’ hair, as well as her own, is too high to quantify.

“Those days where you want to be outside, [instead] focusing on getting their hair ready for Monday,” Rolle says with a laugh.

With all of this weight, symbolism, and history it’s no wonder that hair is so often a feature of so many Black artists’ work.

“Behind every braid, curl, locs, Afro, wave, etc., there’s a story attached,” Williams says. “That’s what makes our hair special. No one in the world has our texture.”

Irene Kannyo is a freelance writer for CITY. Feedback on this article can be directed to [email protected].